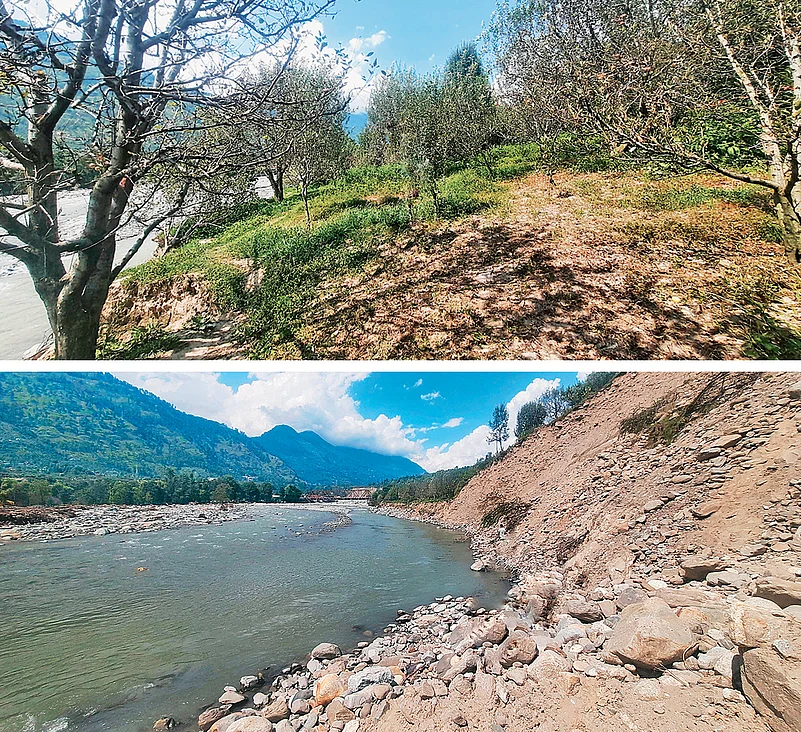

Kunalchand is not harvesting the ready crop of cauliflower this year. “My potato and pea crop was completely destroyed. Gobi (cauliflower) survived but it will all be thrown away. The loss is 80,000 rupees’’ he says. Kunalchand is a resident of Shoja, a village near Kullu valley. Roads on both sides of the village were washed away in the recent floods, cutting the village off from the local mandi (wholesale market). He was still lucky because his land did not get damaged. Panki Sood, another Kullu resident, was not as fortunate. He owns a piece of land close to the Beas River. During the flood, the Beas changed its course, and the land is now the path of the river.

Most politicians throw up their hands and blame these disasters on climate change. They aren’t wrong; the climate is definitely changing. An 84-year-old man in Kullu claims that he has never seen such concentrated rain and hail in his lifetime.

“The unseasonal hailstorms in May wiped out most of the apple crop in the region this year. This is peak apple season and there are no apples.” says Shantanu Kulesh, who runs a hostel in an apple orchard in Shoja. The El Niño phenomenon, combined with changing weather patterns have caused the monsoon rain from the plains to move to the hills. As per IMD data, eight of the twelve districts in Himachal Pradesh received excess rainfall since June this year. Three districts received ‘large excess’ rainfall. This sudden and excessive precipitation is in sharp contrast to higher regions in the Trans-Himalaya, where Kumik village next to the Zanskar River in Ladakh had to relocate due to water scarcity because snow-melt patterns changed. The temperatures in Ladakh have increased, causing glaciers to melt faster. Recent research shows that the Drang Drung glacier in Zanskar is melting three times faster than four decades ago. This increases the risk of a glacial lake flood in the future, which could be disastrous.

“Climate change is a threat multiplier for disasters like the ones we are seeing in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh,” says Joydeep Gupta, the editor of the Third Pole, an online platform focused on watershed management in the Himalayas. “But it is also being used as an excuse for ill-planned development. It is easier to deflect blame onto rich countries for their emissions. It camouflages the fact that roads and buildings have been built without any consideration of the guidelines. Same for dams and bridges,” he adds.

There is a pattern of natural disasters in the Himalayas. Take Uttarakhand: in the last three-odd decades we have seen the 1991 Uttarkashi earthquake, the 1998 Malpa landslide, the 1999 Chamoli earthquake and the 2021 Chamoli glacier flood. The death toll of all these put together is dwarfed by the 5,700 people that died during the 2013 Kedarnath floods.

This leaves the local Himalayan population caught in a cycle of construction and destruction. On the one hand, they are witnessing large-scale infrastructure projects deemed as ‘development’ while at the same time, they are at the forefront of the climate disasters. The newly constructed four-lane Mandi-Manali highway was damaged this August by the overflowing Beas days before it was to be inaugurated. Upon visiting Himachal in the aftermath of the floods, Nitin Gadkari, Minister of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH), suggested that they “build such a strong wall of stone and concrete on both sides of the river that the water won’t go anywhere.” Contrary to this, the 2014 Road Policy of the Government of Himachal Pradesh states that when constructing a road, “There should be minimal interruption to the natural drainage system.”

It seems like the wrath of the floods is a reflection of how damaged our relationship with nature is. It feels like nature is screaming at us, saying, “Learn to coexist with me.”

But we’re not listening.

After the 2013 Kedarnath disaster, Ravi Chopra was made chairman of the Supreme Court-appointed high-powered committee (HPC) on the Char Dham all-weather road project. His recommendations that raised environmental concerns about the project were ignored, and the plans are going ahead to widen the Char Dham road citing military priorities. In frustration, Chopra resigned from his position in February 2022. In his resignation, he wrote “...the directions and recommendations made by the HPC in the past have either been ignored or tardily responded to by the MoRTH.”

“What are you trying to defend? Something that you are trying to destroy?” says Joydeep Gupta, who is exasperated at military priorities being favoured over environmental concerns.

Some regulations specific to the Himalayan ecosystem do exist. For example, the regulations for the town and country planning, Government of Himachal Pradesh, say that in hilly areas, “the overall height of the building shall not exceed 30 metres in plain areas and 25 metres including sloping roof in hilly areas of the state. Twenty-five metres means 7-8 storey structures are allowed in hilly areas. Is that regulation appropriate given what we know about the Himalayas? It sounds wrong even to a layperson. The same regulations also specify that the minimum distance of construction from river banks is 25 metres. However, the head of the Town and Country Planning Department himself admitted that since the river keeps changing its course due to mining activities, enforcing such a rule is complicated.

Are these questionable regulations even being followed? “It is common to see buildings that have permission to build two storeys constructing seven storeys’” says Mohan (name changed), a resident of Shimla. “It isn’t just private buildings, even government buildings are constructed on river basins,” says Joydeep Gupta.

The problem is not just illegal construction but also unplanned construction. It is a geological truth that the Himalayas are crumbly and fragile. We look to European models of construction, but the Himalayas are not the Alps. They are prone to earthquakes and erosion. Landslides are bound to happen whenever there is a period of intense rain, and we need to build and plan accordingly. All of these climate and human-induced changes are leading to changes in the behaviour of wildlife in the region. Kirti Chavan, a conservation biologist says, “The changing climate has reduced the natural diet of bears. They are being forced to search for food in human settlements, thereby increasing the risk of wildlife conflict”.

There is an urgent need to think about what constitutes development. Religious tourism and increasing military presence in mountain areas are paving the way for wider highways and modern buildings. However, are they really what the local population wants, and what the environment needs? In a rare instance of local voices being heard, the people from Bakartse village in Zanskar refused to get a concrete bridge constructed by the government because it would damage the surrounding environment.

The need for people-centric and scientifically backed development in the Himalayas is now more crucial than ever. “The mountain communities are already facing the impacts of climate change. They need urgent support from state agencies to adapt now and factor in climate impacts before any further development in the Himalayan region.” says Aruna Chandrasekhar, a journalist for Carbon Brief, a UK-based climate policy-centric publication.

In 2022, the Environmental Impact Assessment rules were diluted as they sought to remove the participation of people by doing away with the need for environmental clearance for highway projects in border areas i.e., within 100 kilometres of the Line of Control (LOC). An even more recent Forest (Conservation) Amendment Bill introduced this year dilutes the definition of ‘forests’, thereby reducing the amount of land deemed to be a ‘forest’. The Bill also goes on to exempt infrastructure projects in border areas from forest clearance. These policy changes are akin to hurtling down a mountainside with no rearview mirror and no brakes. It is time that we stop the incessant drilling and listen to the voices of science, and of the locals who have been living in these mountains for generations.

3,250 Indian soldiers died in the India-China war of 1962 and 3,843 in the India-Pakistan war of 1971. Climate casualty figures for 2023 are still unclear but a death toll of 5,700 in the 2013 Kedarnath floods make this no less than a war—to be fought by preventing future disasters instead of perpetuating them. We have to ensure that instead of a China or a Pakistan, we don’t become our own worst enemy.

(Views expressed are personal)

(This appeared in the print as The Beautiful and the Damned')

Chetan Mahajan lives in village Satkhol, Uttarakhand where he runs the Himalayan Writing Retreat

Annanya Mahajan is an environmental policy researcher based in New Delhi